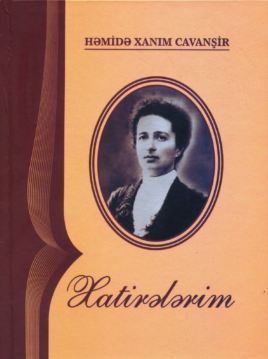

Hamideh Khanum Javanshir's Memoirs of Iran

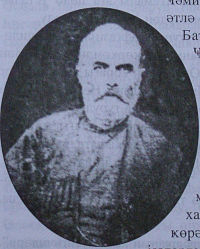

Hamideh KhanumKhanum is equivalent to Mrs. In Azerbaijani Turkish it is pronounced “khanım”. We use the Persian transliteration of all names for the same of greater simplicity, familiarity (Jalil instead of Calil) and consistence. Javanshir was the daughter of Ahmad bey Javanshir, a landlord, poet, historian, and translator from the wild mountain lands of Qarabagh, today a part of the Republic of Azerbaijan occupied by Armenian militias but then simply known as part of the South Caucasus. He was an enlightened landlord on the model of Lev Tolstoy

Enlightenment had its limits in that patriarchal land of blood feuds and tribal warfare. When she was born, her father beat her mother brutally for not having given him a son. Khaterelar, e.g., p. 59. Daughter and disappointed father became reconciled and she became devoted to him. He in turn taught both sons and daughter how to use firearms. He once told her, “There is no point in depriving women of their natural rights and making them like dolls for the strong sex. Depriving women of all their rights will result in their becoming miserable silent slaves without rights.” Khaterelar, e.g., pp. 66-67.

With her parents passing in 1903, Hamideh found herself in charge of the family estate. This was complicated enough with the foes her father had accumulated, but she was faced with crisis after crisis. When warfare between Armenians and Muslims soon broke out, she threw herself into restoring order and communal harmony. Ibid., pp. 98 ff., 108 ff., etc. When famine struck in its aftermath, she organized relief. E.g., Ibid., p. 108..yah When plagues of locusts struck the land around her, Hamideh took charge in each of these crises. Ibid., p. 107. In the meantime, she worked to get her late father’s poems, translations, and historical writings publishedIbid., pp. 100-101. and fulfill her leadership responsibilities to the newly-established Tiflis’ Muslim Women’s Benevolent Society and Muslim Benevolent Society. Ibid., p. 101. She married Mirza Jalil Mohammadqulizadeh, the editor of Mulla Nasr od-Din, the avant-garde journal of the Caucasian Muslim enlightenment.

With the outbreak of the revolution in 1917, famine and banditry broke out. E.g., Ibid., pp. 170-176. But it was with the Bolshevik destruction of the Azerbaijan Republic (which is never mentioned in the memoirs) in 1920 that she and her family had to flee; on the advice of her brother in law, Mirza Ali-Akbar, who had been active in Tabriz during the Iranian Constitutional Revolution, they fled to Iran. Ibid., pp. 201-204. This was not an easy decision, since Iran itself was in turmoil at the time and, as an old friend of her family put it, “The Bolsheviks will do you no harm. But if you run into the Iranian Kurdish bandits, they will show you no mercy.” Ibid., p. 208. Although she herself was having second thoughts about fleeing the Caucasus, Mirza Jalil and his brother, Mirza Ali-Akbar, insisted and the decision was forced when they found themselves targeted by an armed band of unknown provenance.

After a harrowing escape over the Aras River into Iranian Azerbaijan, the party found lodging with one Amir Arshad, a khan who was an admirer of the journal Molla Nasr od-Din. Hamideh writes,

Even Amir Arshad’s enemies speak well of him… He was relatively progressive and literate. He even had claims to being Shah. They used to say that his domain was so safe and secure that if you were carrying a bag of gold on the road, no one would dare touch you. p. 234.

Elsewhere, she wrote of him,

The Amir was middle-aged and very lively. He was tall, handsome, and trim. His facial features were those of a serious and proper man. His wise and deep eyes were very penetrating. All his movements were very measured. It was as if this regal man had been born only to rule. p. 245.

Hamideh describes her hostesses and their quarters:

A marvelous sight was revealed before us. Two ladies were seated on valuable rugs and silk mattresses, their elbows resting on colorful pillows. Great radiant lights lit the room like the sun. One of them, who was busy sewing, was dressed in flowery clothes. She was arraigned in precious stones and gold. As for the other, although she wore no ornaments, her clothes were extremely colorful. For a moment, we gazed at them and they gazed at us, and then we exchanged greetings. They rose to make room for us and had us sit next to them. The ornamented lady was … Khanum Aqa. She was a very beautiful, grand, and wise-looking woman. She was in charge while her husband was travelling. In those days, Iran’s petty khanates did not obey anyone but led their own independent existence and were constantly warring with each other. The other woman was … Aqa Khanum. She was not as beautiful. Besides these women sat a beautiful unadorned woman with masculine features. She was a famous female singer of Qaradagh. She entertained the khan’s women with her beautiful voice and sweet conversation.

Khanum Aqa asked how we were doing with beautiful and delicate words. Before long, a copper tray full of chicken polowPersian-style rice or rice-based stew.was produced. We ate with our fingers from the same tray our hosts did. Khanum Aqa also ordered polow to be brought to be brought to my husband.

We passed that evening with these ladies. At dawn, two pavilions were set up for us by a spring. Another was set up a little way off by a by a waterfall for Khanum Aqa. She invited Munavvar, Anvar, and I to stay in her pavilion. The children who survived Mirza Jalil’s precious wife. That day, she invited our family to lunch. She then presented us with a cow and a pud of flour. pp. 218-219.

In another entry, the author recalls,

This was a mountainous land with vast meadows. The fields were verdant. The atmosphere was fresh and perfumed; the ponds were gray-colored and full of sweet water. We finally felt free. Mirza Jalil’s scowl softened. He closely observed the local population’s way of life and engaged the people in lengthy conversations, jotting things down in his notebook. Of course, the local Kurds took his being Mullah Nasr od-Din literally, believing he was really a mullah. They hadn’t an inkling of a journal by that name.

One day, Mirza Jalil laughed, “Today, an elderly Kurd came, very upset, and pleaded with me to write a prayer for his wife. I refused his plea. He thought this was because I refused to perform this service for free and said, ‘Write it! By God, I will bring you two pairs of socks decorated with flowers.’” pp. 219-220.

In another entry about the local Kurds, the author writes,

The Kurds were very poor. The women and children were dressed in rags. They spoke Turkish with us, but Kurdish amongst themselves. The poor Kurdish women worked both at home and in the fields. The children grazed the livestock, gathered firewood, and helped with the household chores. Each family had one or two cows and a goat. In the winter months, they bring their livestock to a ramshackle stable. The stable door opens into the house and the animals are brought through the house into the stables. There are no other doors to the stable but the one that opens into the house…. This is because theft is so rife.The Kurds only eat millet, barley, and hemp. Their bread is black, but palatable. The local kaymak is particularly tasty. The village Kurds are very rarely able to eat oil. The women churn and while collecting the oil, the khan’s servant immediately bangs on the door and demands it from the woman. If the woman does not believe that he is from the khan, he presents her with the khan’s prayer beads. The women immediately beg his pardon and present the oil without uttering a word. As soon as the servants leave, they curse him behind his back. pp. 220-221. This custom was to be worked up into a story by Mirza Jalil, The Khan’s Prayerbeads.

Aqa Khanum’s father, Shoja al-Mamalek, was at war with Amir Arshad. It was a war Amir Arshad would ultimately win. He overran Samsam ol-Mamalek’s khanate and took Khanum Aqa prisoner. (p. 227) Hamideh Khanum’s party set off for shelter. As she recalls,

On Saturday, July 10 [1920], we mounted our horses and set off. Of our family, Munavvar, Muzaffar, and Anvar were guests. Aqa Khanum rode a beautiful horse adorned with a silken hood, colorful saddle, and a silver bridle. The horse’s bridle was held by a tidily-dressed servant. This was a Kurdish custom, which was observed out of respect and as a token of humility.We followed a scenic winding path through meadows and mountains. The meadows were filled with flowers, which perfumed the air. My horse and Aqa Khanum’s rode side by side and we conversed. On the right rose a tall mountain which surrounded the entire meadow. It looked as if no human could ever have set foot there. Aqa Khanum said that in the past, only her father knew the path there. He built a secret passage there and a house with a wind-driven water pump so in case he suffered a defeat in battle, he could spirit his family there. Aqa Khaum said, “And now, we are going there to take shelter if Amir Arshad comes. We’ll bring you with us. We will have sufficient provisions there.” p. 222

Later, she recalls,

One day, Khanum Aqa brought us sistersAs she called her friends. to the mountains where their winter quarters, called Gavchin, were, for a party. It was even more enchanting than Aliabad. Where Hamideh’s party was first quartered. We were grateful to spend three days there, after which we returned.

Qizqayit Khanum spent the whole day with us. She joked, told amusing stories, and sang beautifully. She was a very interesting person. She was 35. To avoid men, she refrained from marrying. She was a singer. Khans’ wives could not get around forever. She would certainly no longer be able to ply her trade in family circles. In addition to singing, she worked alongside a khan’s wife as a manager and a butler. She rode a horse like a man and travelled the length and breadth of her domain, supervised, issued instructions, and placed orders. She was a terrific little Amazon. p. 227.

Ultimately, the party headed on to Amir Arshad’s stronghold. This was in Ahar, a city which “follows neither khan nor shah, but is ruled by its own laws and administration.” p. 237. Hamideh Khanum meets Amir Arshad’s wife:

A minute or two hadn’t passed when a tall, beautiful lady dressed in the European mode, in an open, colorful outfit, entered. She was not veiled; only a summer scarf covered her head. This was Amir Arshad’s wife…

[Her] name was Ismat ol-HajiyyehThe Chaste of the Female Hajjis. Khanum; after she’d made the pilgrimage to Mecca, she took the title of hajiyyeh… The Amir’s wife knew that I don’t avoid men, that I work, that I live an independent existence, that I own my own property, and that I manage my own expenditures. She spoke to the Amir about this. The Amir sent his wife to ask me to speak with him. One morning, Amir Arshad came to speak with me. He spoke very sweetly about my arrival. He made it know how sorry he was that he was not informed about it, and said that had he known, he would have come out to greet us. p. 244.

Ultimately, the party reached its destination in Tabriz, the capital of the province of Azerbaijan. Hamideh Khanum writes about what happened on their arrival:

Mirza Ali Akbar had sent for a coach, and it was waiting for us at the bridgehead. Mirza Jalil, myself, Munavvar, and Anvar stepped inside. The driver had to wait, since women could not enter the city in an open carriage… Just then, a horseman approached and dismounted. He politely explained to Mirza Jalil that he should get out of the coach, since in this country, it is forbidden for men and women to get into the same coach. Mirza Jalil replied that these women were not strangers; one for them was his wife, the other, his daughter. The horseman said that not even mahram womenWomen of such close relationship with a man that he is permitted to be alone with her, such as a wife or a sister. were allowed. He even pointed to or nine year old Anvar and said, “Even this boy will not be permitted to sit in the same place as the women.” Mirza Jalil was at a loss. He glared at the horseman. He understood that, although he was talking with Mullah Nasr od-Din, he wasn’t kidding. Mirza Jalil, not completely understanding the situation, asked, “Fine, so where should I sit?”

“Ride on my horse.”

“But then where will you sit?”

“By the coach driver.”

“Fine. In that case, I will sit by the coach driver with my own family. You go on your horse.”

Mirza Jalil hoisted with difficulty his girth onto the coach driver’s seat and sat down next to the driver. He then turned to us and said, “Seat Anvar between us and cover his head. No problem. When the time comes, we’ll change places.” p. 249.

Mirza Jalil’s trail of biting anti-clerical satire caught up with him, as he faced persecution from the sanctimonious targets of his barbs. He sought protection from them as a Russian subject, p. 254. and soon the Russian consul’s family and his family became fast friends. The consul remarked on the town’s profound conservatism. “They say that Tabriz has its own God and its own sanctities. It keeps them and will not permit them to be changed. New laws and getting rid of the old system are impossible. Some have struggled to make certain changes, but all they got for this was to lose their lives.” p. 255.

Hamideh Khanum travelled around the city, observing the flagellation ceremonies marking the holy month of Moharram. She also visited the Armenian quarter and reported,

The city’s Armenian quarter bore no resemblance to the Muslim quarters. In the Armenian quarter as opposed to the Turkish [Iranian Azerbaijanis] quarters, the windows in the houses opened onto the street. There were luxurious and beautiful decorated shops, pharmacies, clubs, and a clean public bath. The only place in Tabriz in which there was a theater was the Armenian quarter. pp. 265-266.Mirza Jalil had a terrible time getting permission to resume publication of his newspaper in Tabriz as planned. Mokhber os-Saltaneh, the new governor there, was very antagonistic about having a Turkish-language newspaper published in Tabriz, even though, as Mirza Jalil explained, there were four Armenian newspapers published in that city. At first, he refused to countenance any such newspaper. He then agreed to allow a Turkish newspaper to be published on the condition that it include an editorial in Persian. Mirza Jalil held his ground, and this condition was dropped and the newspaper was published in Azerbaijani Turkish alone. pp. 267-268, 270.

Aside from the language issue, Mirza Jalil’s newspaper’s outspoken exposure of the local government’s general slovenliness enraged the governor, who tried to shut the newspaper down on these grounds. However the newspaper had friends places high and in low. The governor’s chief aid (kargozar) was a great admirer of it. This, and threats to embarrass the governor before Ahmad Shah and international public opinion led the governor to end the ban on its publication. p. 273.

The journal focused chiefly on moral improvement rather than language or social or political issues. Its article on dens of immorality, where men would drink and frequent prostitutes, led to the local government closing them down and deporting the women who worked there.

This article caused a great explosion in Tabriz. Mothers in particular were very pleased with it and its impact. Some women came to us and begged me to convey their profound gratitude for it to Uncle Mullah. They said that their husbands would take all their profits after closing up shop for the day and go to these same houses of disrepute and have a grand time and get drunk and return in the morning in a stupor, leaving their families poor and starving.

When news spread in the bazaar that the journal had been closed, the people were enraged and began to protest. Some shouted, “They won’t let Uncle Mullah tell the truth! If so, we won’t open our shops and work!” pp. 273-274.

One incident Hamideh Khanum recalls is:

There were many Caucasian refugees in Tabriz. Many of the female Caucasian refugees wore their own Caucasian chadors. But after they settled in Tabriz, some of them wore the traditional Tabriz chador, including the bicheh, like the Iranian women. It is a black face covering of thick gauze, the sort a parasol is made of, which covers the entire face. One refugee was Tarlan Khanum Kangarli from Nakhchavan, along with her husband and family. She was one of the women who wore a bicheh along with her black chador. She was a tall, stocky, and beautiful woman. One day, she went to the gated Amir Bazaar with her servant to do some business. There, a man who was passing by her suddenly pinched her on the side. The woman immediately turned and grabbed him by the shoulder and fetched this rude man one or two smart blows on the crown of his head, sending him sprawling to the ground, stunned, after which she started kicking him. Her servant helped her. The two women together beat this wretch to within an inch of his life. While kicking this rude man, Tarlan Khanum shouted from behind her bicheh as if to drive out the Iranian men’s foolish custom of pinching women in public and embarrassing them. A crowd gathered and the farrashes arrived. It was as if no one had the courage to approach Tarlan Khanum and save this crushed rogue. Tarlan Khanum kept kicking the rude man, screaming, “You made these Iranian women miserable and wretched and intimidated. You use this to pinch them in public where ever they were. In order to protect their honor, they don’t go out. Aren’t you angry at this? Do you think Caucasian women will also shut up and not speak out? Next time, I’ll come to the bazaar with a pistol. Let someone be so bold as to offend me. I’ll shoot him.” pp. 279-280.Tabriz women were no slouches, either. Ahmad Kasravi’s celebrated History of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution carries a report on a mob of starving Tabriz women who lynched a wealthy landlord. (pp. 354-355)

The memoirs had their own history. They were written in the mid-1930s. Adalat Tahirzadeh, “Chaghinin Lakasiz Guzgusu” in Khaterelar, p. 28. According to Mehriban Vazir, the woman who performed the herculean task of pulling together the various pieces of these memoirs into a coherent whole and translating them from Russian to Azerbaijani Turkish, when Mir-Ja`far Baqirov, the murderous dictator of the Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan, tried to bully the author of the memoirs into devoting her work to the sort of sycophantic praises he was used to, she spurned him. Mir-Ja`far had the offending memoirs consigned to the archives, where they languished until the well-known Soviet Azerbaijani scholar Abbas Zamanov published a translation into Azerbaijani Turkish of the part of this work devoted specifically to Hamideh Khanum’s illustrious husband. This translation included ideologically-motivated alterations. The full work had to wait for the collapse of the Soviet dictatorship. Mehriban Vazir, “Hamideh Khanum Javanshir va onun Khatirelari,” Khaterelar, pp. 7 ff., 20-22 and Adalat Tahirzadeh, “Chaghinin Lakasiz Guzgusu” in ibid., p. 28.